250 West 24th Street #GBE

A unique and compact apartment provides the opportunity to create the perfect one-bedroom unit with adaptable spaces defined in part through a refined palette of white materials and white oak paneling.

A garden level apartment in Chelsea, on the west side of Manhattan, had been on the market for 9 months as a result of its odd layout and challenging existing features. After years of on-off looking, the decision to purchase was immediate. The peculiarities that had discouraged other buyers (exposed foundation walls and large structural columns) had the opposite effect on myself. Upon first seeing the apartment, its potential was clear and significant.

The unit was newly constructed at the garden level of a 1930’s co-op building. The floorplan, listed at 720 sf, had two entrances – one from the internal corridor of the building and one from the garden courtyard – with an entry corridor using 180 sf of that total. Secondly, in constructing the apartment, a 22” high and 14” deep concrete footing had been poured around the interior perimeter. This footing detracted from the usable floor area and made using the perimeter very difficult. Additionally, as a garden-level unit, the apartment had relatively few windows and low light levels.

As the renovation progressed, the peculiar characteristics caused the apartment to function as a laboratory. Through solving the spatial problems, I’d have the opportunity to investigate specific architectural and design interests, themes, and ideas:

- design can unlock the potential of any space

- all spaces have architectural potential

- design is democratic

- program is an effective architectural driver

- the one-bedroom can be idealized

- space can and should be easily transformable

- standard materials can feel special

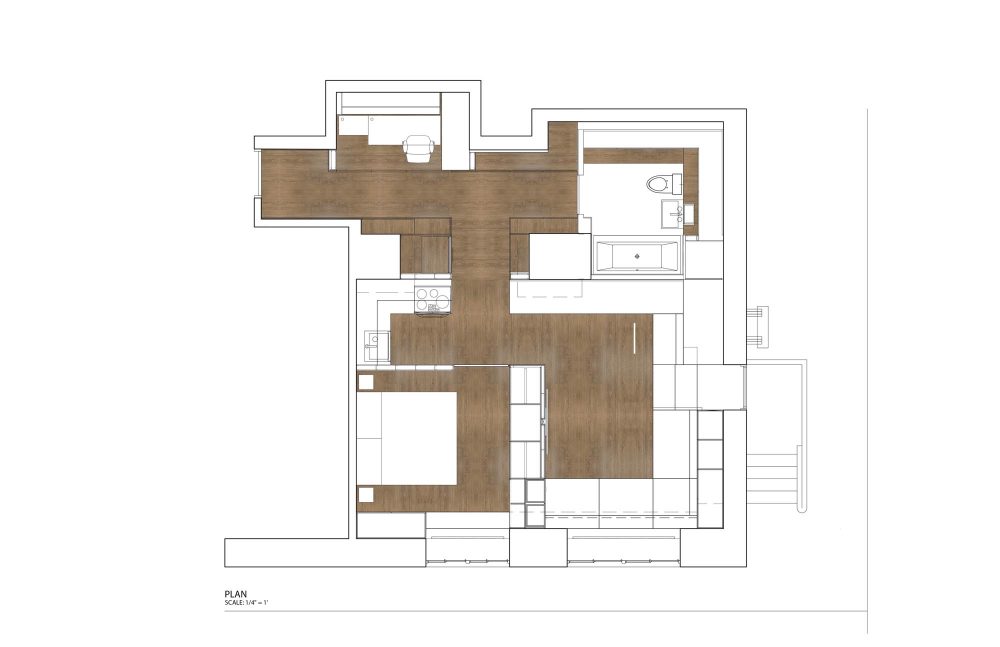

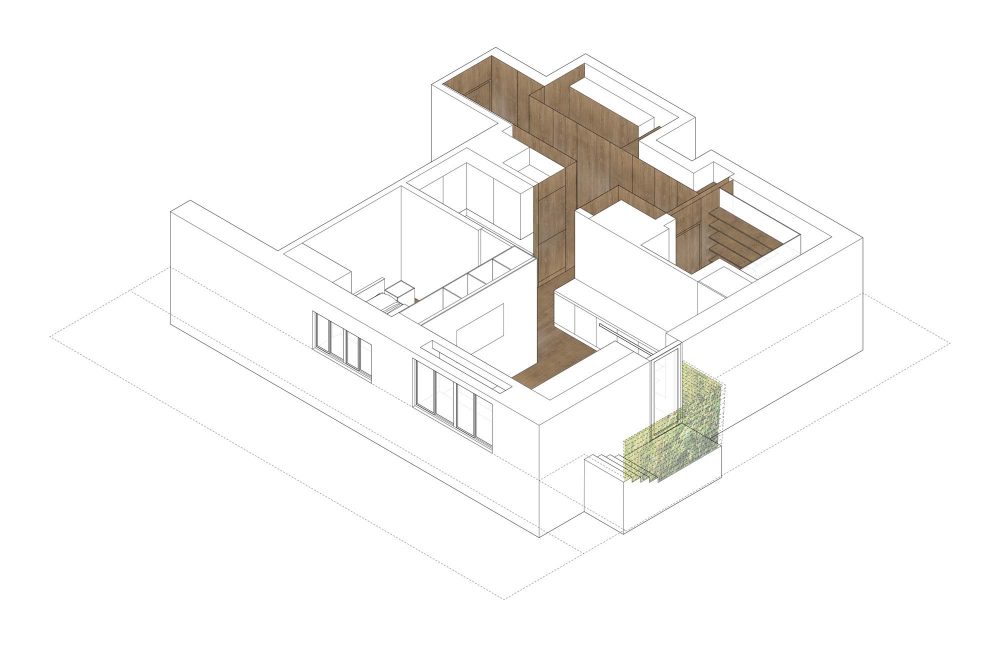

The primary issue was the apartment’s irrational spaces. Fortunately, the solution to this problem also resolved what every small apartment lacks – storage. The concrete footings would be built-over with furniture and floor-to-ceiling cabinetry, aligned along the perimeter edge. Next, a partition wall was necessary to separate a bedroom from the living space. By thoroughly understanding the program and functions, the two spaces were able to be optimized and kept as small as possible. This allowed the partition wall to be thickened and hollowed, sacrificing a small amount of floor area but gaining a significant amount of storage. What seemed to be the most unfortunate of the detractors eventually yielded the most successful outcome – simple spaces with coherent volumes and lots of storage.

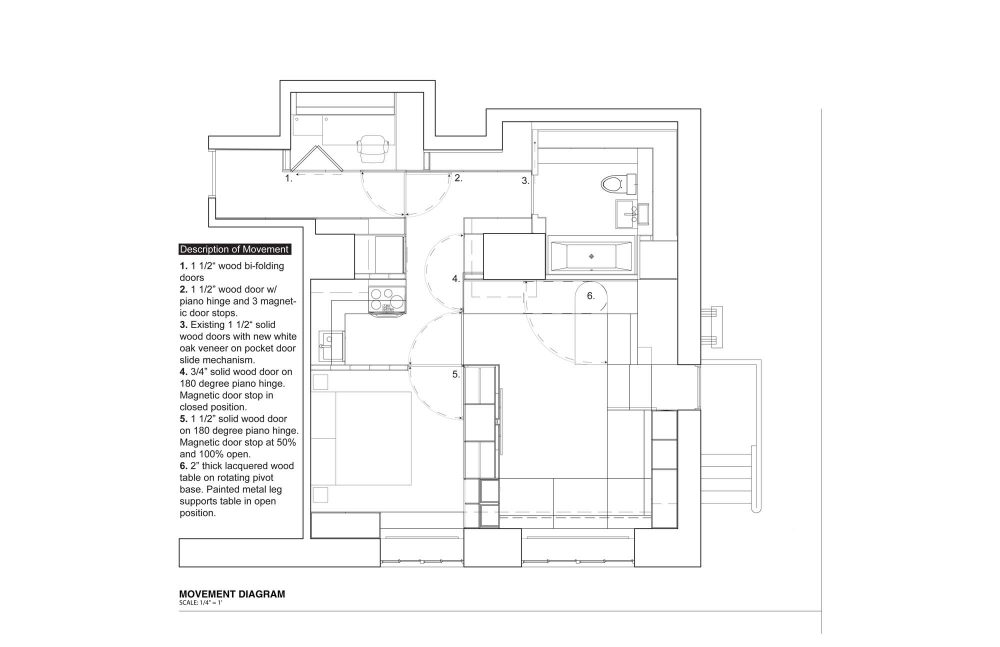

With the space clearly defined, the next step was to outfit the unit with the ideal one-bedroom program – public living space, dining, working, a kitchen, a private bedroom, guest quarters, and a bathroom. We developed this program by thinking through all potential occupancies of the space as well as all potential experiences for the occupants. This all concluded 7 functions in 700 square feet. Physically acting through activities and motions within the space informed our approach to the layout and also how we detailed components such as the doors and furniture.

For this and all small spaces, adaptability would be essential. Designing the perimeter cabinetry yielded a small walk-in closet in the over-sized entrance hallway. By expanding the closet to house a Murphy bed and coordinating the width of the closet door with the width of the hall, the space could be easily privatized for weekend guests. They would even have their own entrance. Similarly, a dining table would never function as a permanent static element. Instead, a pivoting table was designed. Set on a large ball bearing, the table swings out from the perimeter cabinetry into the largest of the interior volumes, the living space, and transforms the volume for special occasions. Additionally, the cabinets at the fixed end of the table were optimized for quickly and easily storing working materials. This allowed for 3 functions – gathering, dining, and working – to fit in a 224 square foot area.

When finishing the apartment, I chose a minimal palette less for stylistic reasons and more for function. In the small space, it was important not to be visually overwhelmed. One half of the apartment would be white, bright, and open; the other half would use white oak veneer to create warmth and comfort. Keeping with this duality required complexity and intrigue to be designed in a nuanced way that is more appropriate for small spaces. Kazimir Malevich’s ‘Suprematist Composition: White on White’, where an austere surface is balanced by textures created by the artist’s hand, was an inspiration for this decision. White lacquer, fabric, terrazzo, stone, matte paint, and metal panels were all used alongside each other to create a variety of texture within a palette of white. For the oak paneling, the strategy was to finish the wood as minimally as possible, using only oil to enhance the grain and protection. Additional elements, like the steel, recessed cabinet door pulls, and the deep, open shelving in the bathroom interact with light in ways that are subtle yet effective. Light, in general, was a challenge in this space. With 8’0” ceilings and at the garden level, direct light is limited. I chose LED fixtures and designed hidden up-lighting anywhere possible. At the windows, light pockets were carved into the perimeter wall to reinforce the natural light with LEDs. The tops of cabinets have built-in light boxes throwing light onto the ceiling and expanding the perceived height of the space.

While some of the interventions in the project may seem to reduce the apartment’s total usable square feet, each carefully designed micro-gesture makes the space infinitely more functional and pleasurable. Before the renovation, the apartment had a single, large, slightly ambiguous space in which all functions and programs had to somehow fit and find harmony. At the same time, existing features would have proven challenging to any attempt to use the space in its unaltered state. Through dividing the larger ambiguous space into two smaller, more defined spaces, the apartment better reflects the realities and needs of a single-person household. In this way, design, based on the careful research of program and lifestyle requirements, has successfully enriched a space beyond recognition of its earlier uncertainty.

This process was driven in large parts by data on the housing market in New York City and beyond. Americans and Europeans are increasingly living alone, thus, there is a growing demand for smaller units in New York City. Looking at recent Census data, particularly the 2011-2015 American Community Survey, of the 3,113,535 housing units in the city, only 7.1% are studio apartments, and 30.6% are one-bedroom units. Contrast this with the number of one-person households (32.5% of the same figure) and two-person households (27.9%), and a clear imbalance presents itself: market share for one-bedroom or studio units is 37.7%, while 60.4% of all households potentially look to occupy these types of units leaving a total deficit of 22.7%.

Typically, this problem is approached with the solution of building new apartments, but as developers seek to maximize their profits, fewer small units are being built. In the current market, developers building new units stand to make a larger profit from building two or three bedroom units in place of studio or one-bedroom units in the same building. One exception is the construction of New York City’s first micro-apartments at 335 E 27th Street. These units - below the 400 square foot minimum mandated by the city - are not only small, but expensive, with a rental pricing of $97 per square foot. Not without their critics, these unit types are having an effect both on the city’s housing market, and people’s expectations from a new build apartment.

With the majority of all New York City housing units having been built before 1980 (85.1%), it becomes clear that the reality of the situation calls for a refocused approach prioritizing the renovation, redevelopment, and adaptive reuse of the huge quantity of existing structures in the city that do not currently adequately meet the demands of today’s users. In this project, we propose a way forward for the city, with a concrete physical response that is grounded in real, current sociopolitical-economic issues, and based on contemporary precedents.

Project Shown: 250 W 24th St.